Kelly, why don’t we move from 413 to the couch area? is installed in two locations. First, visitors enter a big empty room, 413 in the CIT building at RISD, where they find a very loud noise from the AC system; and second, they move to a couch installed on the other side of the same floor. A long corridor connects the spaces. In the entrance of both spaces a sign shows the title of the installation: “Kelly, why don’t we move from 413 to the couch area?”

The entry point of the piece is the title located in front of room 413’s door. When the audience reads the title card, they discover further that they should keep silent throughout the process and take the first step by spending two minutes inside the room. After reading it, the visitors enter the room as a group. It’s a big empty space; a beam of light enters though the window and there is nothing to look at. The visitors inside the room, no more than 20 persons, only pay attention to the white walls. The sound becomes more and more important as time goes by. The noise is strange; it is the loud, annoying motor of an AC system next door, but this is not explicitly noted. Suddenly, the door opens; the two minutes are over.

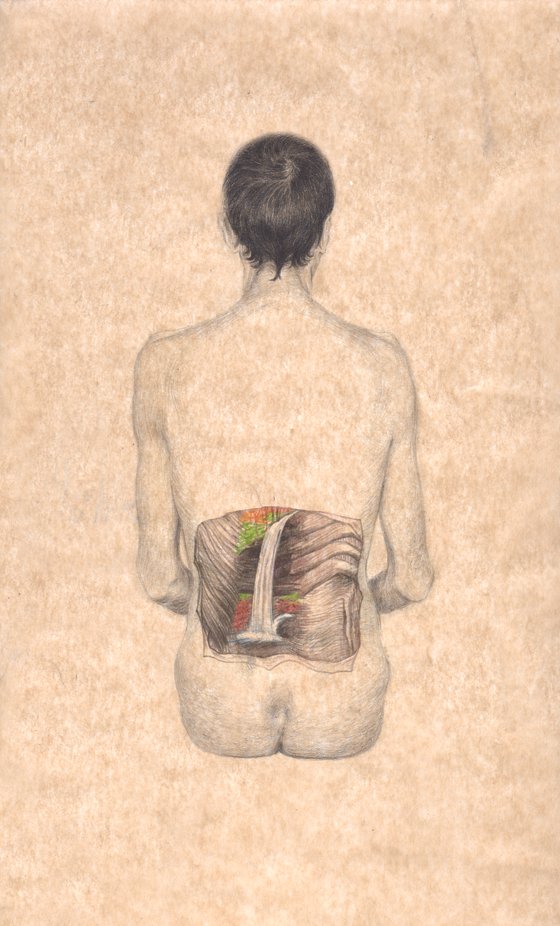

Visitors move to the other corner of the building in complete silence. When they arrive, they read another sign; they have to sit on the couch for other two minutes. Each visitor is given a piece of paper with his name and his time slot. They sit down in couples. The couch is vibrating. It doesn’t produce sound but the movement is intense. The vibration is dirty, rough, and at some point registers as similar to the sound experienced moments ago. The body vibrates with the rhythm of the noise. The back becomes more present. After two minutes, the visitors are invited to give their places to another two people.

This installation is a new direction from my other works around the topic of the body sensations. It is framed in some ways in relationship with James Turrell’s pieces in which ritual plays an important role.

The differences with my other works lie in three specific elements: the ritual, the slice of life provided in situ and the kind of sensation that this frequency generates. The ritual in this piece is very rigid and affected by my presence as master of ceremonies, conducting the visitors from one part to another of the building, handing out the paper, sitting and watching them. Unlike other pieces, the visitors cannot talk until all of them have experienced the piece. The lack of social validation of what they feel forced them to trust their own sensations as a unique element of judgment. As they spent the same time in both places, most of them established a relationship between both experiences.

The second element has a crucial importance in the success of this piece. It’s the first time I provided a shared moment of everyday life; rather than asking the audience to walk in my shoes I ask them to walk in their own shoes. They have their own experience and then they feel their own sensation through the body. Their hearing system and skin have completely different thresholds. I just switch the source of the stimulus, the sound, in order to show them the effects of the low frequencies in their bodies.

This freedom that I give to the audience allows for an unguided sensation. Each person negotiates with its own body what they are feeling in both spaces. I don’t know the answers I just try to focus their attention in the fact that uncomfortable vibration is the same noise that they listened before. Kelly, why don’t we move from 413 to the couch area? expresses a negative reaction to the unpleasant body sensation a peer was feeling in room 413; on the couch, this becomes something that our ears cannot hear but our body can feel.

Images: Plan of the Installation, Detail I, Detail II, Physical Sensation.